NEWSLETTER

Fire up the presses!

All good things must come to an end.

No, no. Good things come to those who wait.

Yeah, that’s the one. No idea who said that or if it’s even true. But I’ve never been good at sitting around, waiting. Though I do tend to play the long game.

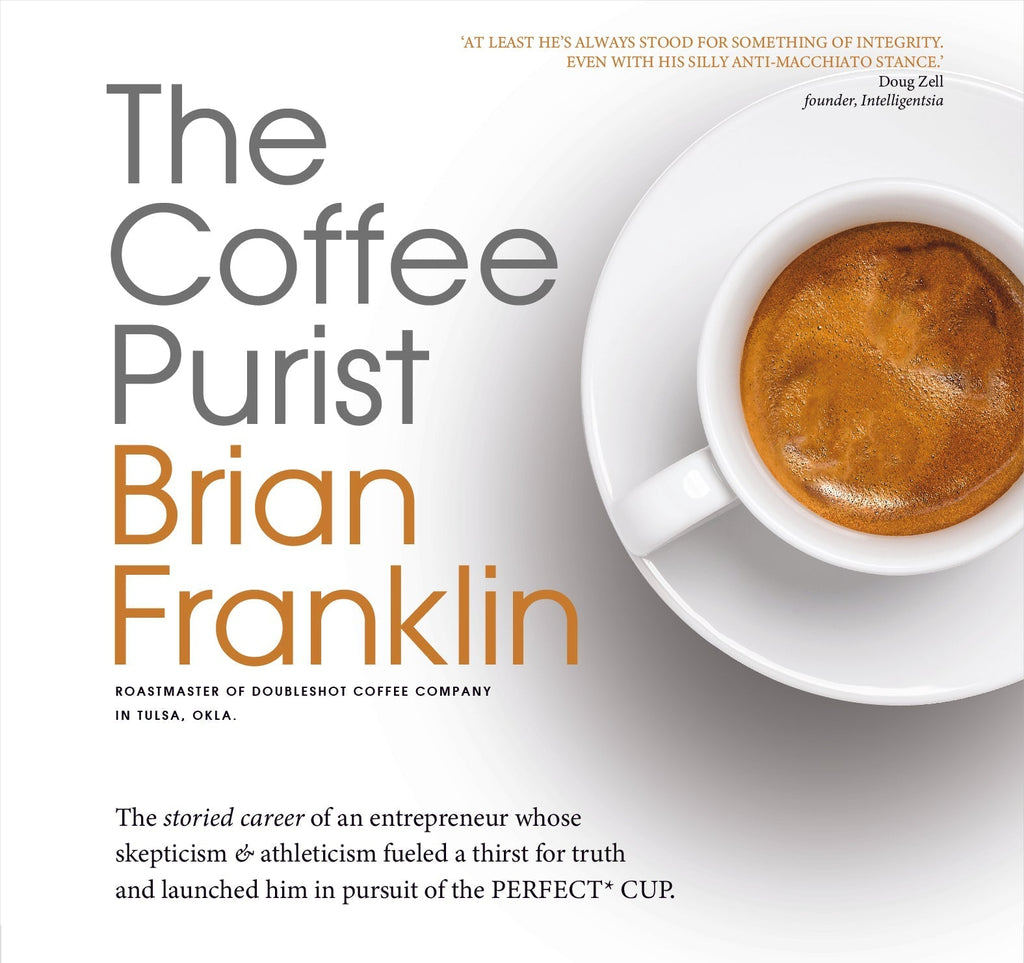

Nonetheless, I have some good news and some not-so-good news. We are finally finished with the book. After many, many rounds of edits and a run-through with a professional proofreader, countless photo edits, a few re-writes and additions, layout and design modifications, we’re ready to let it be.

We’re well aware that you will find errors and typos, and that we’ll likely be disgusted with ourselves for messing something up. But realistically, this has evolved into a huge, compelling, and beautiful project. It’s the first thing people say when they flip through one of the early proofs we had printed and bound. “It’s beautiful.” That’s thanks to Mark.

The book is full of photographs going all the way back to 2004, and even earlier. Around four hundred in all. It’s over 160,000 words. You knew I was wordy, but no one would’ve predicted I could put together that much prose. I can only hope y’all still think it’s beautiful after you’ve read it.

As for the not-so-good news, we’re struggling with the printing process. While initially intending to print it in the U.S., prices are way too high. Canada isn’t much better. India was an option, but shipping and tariffs have taken that printer off our list. So as much as our president doesn’t want us to, we’re dealing with a printer in China. Normally tariffs on books are zero. But you know nothing is normal these days.

Through it all, we’re going to get there. It’s merely a handful of decisions about gsm, coated vs uncoated, dust jackets, and endpapers, and we’ll be at the finish line. As always, we appreciate your patience and hope to have the book in your hands by November. THIS November.

I posted a couple chapter layouts to tide you over at purist.coffee (click the link). And if you haven’t kept up with the latest press or coffee weirdness going on over at the purist site, be sure and check that out.

Brian Franklin, Roastmaster & author

Let the games begin

A long time ago, Isaiah and I created a game that turned into an experiment and ultimately led me to realize I was watching a study in human behavior. It was such an eye-opener for me that I had to go home and sit down in the quiet to think about what was actually happening. It’s possible that you played this game during the brief period in which we conducted it. And if you were lucky enough or smart enough or psychic enough to figure it out, you might’ve even won.

In honor of the DoubleShot’s twentieth birthday, we’re bringing back the game, under different conditions. So you get another shot. All day on March 5, you can come in and pay a buck to play. Here’s how it works: You’ll examine a jar full of coffee beans and use all your skills and intuitions to figure out how many beans are in there. Play as many times as you want. At the end of the day, we’ll tally up all the entries and whoever is closest will win $100 gift card to use in the cafe.

I wrote a chapter in The Coffee Purist about the original game Isaiah and I created, and everything I learned watching people play. The book is currently available for pre-purchase. Read about it and follow the link at Purist.Coffee.

Make mine a Dubbel

DoubleShot and High Gravity team up for birthday beer.

People say “beer” and it leaves us speechless. There are ale people and lager people. While not ones to judge, we’re definitely ale people. So it’s fitting that, for our 20th birthday smash, we’d serve an ale, one brewed especially for the event.

Dave and Desiree Knott of High Gravity Brewing Company have outdone themselves, creating a classic Belgian dubbel that hits all the right notes, in the spirit of some of our favorite ales—Westvleteren 8, Westmalle, New Belgium Dubbel, St. Bernardus Prio 8, Rochefort 6, the list goes on. We taste toffee and green apple, white grape and Rainier cherry. We taste … celebration.

For the party, we’ll serve our new DubbelShot ale in pint goblets, and sell it to go in four-packs of 16-ounce cans. It comes in a can but we recommend pouring it into a glass, maybe that Chimay tankard that’s gone idle for a while. Whatever vessel you choose, drink it at 50°F.

Ale, yeah.

Rhymes with plenty

How does one celebrate twenty years in business? Well, all day, for starters.

Mark your calendars, save the date, and all that: Come March 5, the DoubleShot turns 20!

Did you just do double-take? We sure have. Did anybody believe the day would come? A milestone, to be sure, in the history of our little company, and in the annals of Tulsa coffee.

The fun begins at 7am when we OPEN the doors. Be among the first 20 customers and receive a commemorative gift from us, one we’re keeping a secret but WAY better than your average swag. We’ll have events all day celebrating the past, present and future of DoubleShot coffee—a string quartet venturing into heavy-metal turf, coffee tastings that even we’re excited about (and we taste a LOT of coffee), the bluegrass sounds of Grazzhopper, games of chance (and maybe some skill), a self-led Rookery tour, all kinds of fun stuff.

Then we’ll SHUT at 6p and reopen at 7 to really up the ante, starting with our own DJ Jolly on the turntable, followed by duo of Beau Roberson and Dustin Pittsley. We’ll have plenty of food, beer and wine for sale, gratis coffee on drip, and our espresso bar open for the so-inclined.

To get a piece of the action, you need a ticket. It’s free, but only available on our new app, so download yours now. Come early, stay late, represent.

Now, at an app store near you

At long last, you can order coffee and more on the new DoubleShot app.

“You guys need an app,” everybody’s always saying. Well, everybody happened to be right, we just had other fish in the frying pan. It hasn’t been easy, ordering coffee while driving up Boulder Avenue, poking away at the buttons on the curbside page of our website. Sweet.

Yes, it’s been a long time coming. No more ordering online through a web browser, no more standing in line waiting your turn to tell the cashier what you want. Now you can order coffee beans, food, and drink on the DoubleShot app for curbside or in-store pickup. Put money in your wallet so you don't need your credit card. Get live streams from events and coffee travels. Find hidden XR triggers that activate short videos. There's a lot to unpack here. Download and start exploring.

And, as if convenience wasn’t incentive enough, the ONLY place to get your ticket to the DoubleShot 20th Birthday Party is on the app. Download now and let the fun begin.

The Birth of the Coffee Nazi

The Tarrazú and Candelaria rivers converge into a boulder-strewn flow at the foot of Hacienda La Minita, disappearing into more coffee country and carving up the highest elevation and highest quality coffee-producing regions in a land of coffee excellence. This entire area is known as the Tarrazú region, undulating between towns named for saints: San Marcos, Santa Marta, San Lorenzo, San Carlos, and all the other santos. In fact, the larger area encompassing Tarrazú and Dota and León Cortés Castro (named for a former president of the country) is called Los Santos because of the substantial number of towns named for saints. And the Tarrazú part of that is a veritable Mount of Olives, producing some of the finest coffees on the planet.

Every year when I visit La Minita, I lace up my running shoes and endeavor to run from the farmhouse at 4,500 feet down to the confluence of the two rivers at 3,000 feet, and back up in less than an hour. It’s hard to say how far it is. I’ve clocked it at both 4.5 miles and then 5.6 the following day. GPS can be sketchy on steep, winding mountain roads. My friends on the farm, Jose and Jhonny, always marvel at my runs, and probably wonder why the hell I would actually do that, asking how long it took me (and remembering how long it took me to ride my bike on that path back in 2005). This year I knocked down a lung-crushing 49 minutes.

The Candelaria River cuts the northern boundary of the farm and the Tarrazú marks the southern with a pie-shaped point on the western end where they meet and the Tarrazú empties into “Rio Grande Candelaria.” None of this is important except that these physical features on the landscape mark a separation between this and that. This side of the Candelaria is La Minita, while the other side is NOT La Minita. The Tarrazú marks the division between La Minita’s agriculture side and its processing side. Cross the Tarrazú in the back of a coffee truck (or on a cable suspension bridge) and you’ll find yourself at a large factory where the coffee cherries harvested on the opposing mountainside are stripped of their skins, washed of their meat, and dried in their shells before being sorted by density, size, color, and consistency. It’s a dramatically different scene from what’s happening among the shrubby Caturras and Typicas where Ngäbe-Buglé Indians from the comarca in Panama hand-pick ripe cherries from spindly, intertwined branches and drop them into baskets tied around their waists.

There are divisions, but the whole system works together toward the same end: to produce the best coffee we know how. Lest you think the humble harvester isn’t important in this whole quality calculation, let me explain another division: ripe vs unripe. Recolectores, as they’re called in Costa Rica, have a tough job. They’re required to only pick the ripe coffee and leave the unripe or half-ripe coffee on the tree. Oftentimes ripe and unripe cherries are in a large cluster all together on one branch, so the harvesters must dexterously pluck the red and leave the green. Each year at La Minita we taste the quality separations performed at the mill: first quality, second quality, third quality, and unripe coffee. The cups are both distinct and degrading. Only around 15% of the coffee on the farm makes the cut to be called “La Minita” and everything else is distinctly NOT La Minita. I once asked the head cupper, Sergio, what the most important part of the entire process is for ensuring the highest quality coffee. Without hesitation, he said, “Picking.” Because once the skin is stripped off the coffee cherries, you can never be sure that the green coffee will get sorted out, even through the fifteen (repeat: fifteen) quality separations that take place in the mill. So, arguably (and according to one of the most talented coffee tasters in the world), the coffee pickers have the most important job in ensuring top quality. Because the distinction between this and that is dramatic.

The first time I went to La Minita, that entire world of coffee production opened up to me. Prior to my visit, I’d only read about it and looked at pictures. I spent a few days on the farm and then explored the broader Los Santos region on my mountain bike. And during that time I came to know coffee from an entirely different perspective. I came to know the labor. I came to know the meticulous nature of it all. And I came to know a lot of the people involved in the day-to-day operations of the farm. And I came away with an immense appreciation for the work those people do on coffee farms and mills.

I came home from that trip and roasted another batch of La Minita, this time with more pride. Roasting coffee precisely is a very difficult task. La Minita makes it a bit easier by creating a near-perfect coffee that roasts consistently from batch to batch. But for me, there’s no “dark roast,” “medium roast,” or “light roast.” There’s a specific roast profile for each coffee, and to my palate it’s either over-roasted, under-roasted, or it’s roasted correctly. The divide is as stark as the Tarrazú River – you’re either on the farm, at the mill, or you’re in it. I vividly remember weighing out a portion of freshly roasted La Minita to brew, opening the hopper of the grinder, and hesitating before pouring the beans in to be ground. I stopped to make sure everything was right: the grind size, the weight, the brewer was hot and ready to go. The faces of all my new friends at the farm flashed through my mind and I remembered the hard work required by so many people in order to get this coffee ready to brew.

But I was on the other side of a much larger chasm than Rio Grande Candelaria. I live in a country where convenience is key and quality is scarce. I live during a time when information is doled out in tiny bites and greed inspires dishonesty and misinformation crafted to hawk sub-par wares to the unwary. I was serving a clientele brought up on the worst coffee and educated in Burger King-esque customer service. I’d already put my foot down to quash many commonly accepted coffee shop misbehaviors, refusing to let the customer disrespect me or my staff, the commitment I’d made or the product I believed I’d crafted properly. But this was different. The coffee I’d been handed was already front-loaded with sacrifice and meticulous efforts, and now some of the people involved in that were my friends. And I’ll be damned if someone is going to disrespect the hard work and sacrifice of a friend.

On our latest tour of La Minita, Mark took his first trip to a coffee farm and I tried to see it all through the lens of the uninitiated. I watched as it all unfolded before him as it had for me in 2005, and as it began to sink in we talked about what happens to this coffee back home. He said it made him want to stand next to the bus tub and drink whatever coffee was leftover in people’s cups. “It’s insulting,” he remarked. And that’s when it hit me. He got it. He understood what I felt when I came home in 2005. When I stood behind the counter and watched customers pour milk and sugar into this perfect cup. Stood and listened to customers who didn’t care about the coffee, who asked me to pre-grind the coffee, and never seemed to notice the sweetness in the cup from the pickers who only harvested ripe cherries and millers who sorted out the floaters and the quakers and the empties and the insect-damaged. The room full of ladies hand-sorting out the discolored or misshapen. It enraged me because it wasn’t just my craft they were disrespecting, it was the labor and care of hard working people 2,800 miles away. And that’s when they started calling me “The Coffee Nazi.”

I started this business to share excellent coffee with people. With as many people as possible. And then they said I cared more about coffee than people. But that’s because they don’t know the people behind the coffee, like I do. And if you don’t care about those people, there are a lot of other places you can drink coffee in Tulsa. Places where they don’t know where their coffee comes from, and don’t care. Places where they pretend to know the farmers but copy and paste from their broker’s website.

When I first flew to Costa Rica, I came back a different person. And this year when I ran down to the confluence of those remarkable rivers, I ran back up into a different region. Into Los Santos, a change in demarcation that excludes La Minita from the Tarrazú region altogether. Excludes the entire Tarrazú valley, actually. Like excluding Olivet from Judah. It’s a bastardization in nomenclature, but what’s in a name? They called me a nazi. I’m not a nazi; that bastard León Cortés Castro was. I’m more like a santo.

The Fruits of La Minita Labor

The way from San Jose zigzags southward out of the city through the pass of the Cerros de Escazú toward the Tarrazu valley. Through the window of the shuttle I watched as we meandered the narrow streets, hardly realizing that the road would only grow more precarious.

Next to a car wash that looked nothing like the carnival rides of our own launderers stood a sleek new McDonald’s, stark amid all the garages and fruit stands, bars and impromptu futbol pitches. Everything—roosters, fenced yards, unattended kids—felt casually close to the curbless roadway.

Jim, our driver and host, had driven this road over the mountain Lord knows how many times. A versatile guy, Jim, he told a tale of how there ended up being so many Italians in Vera Cruz, the one in Mexico, while managing to avoid several packs of cyclists tackling the switchbacks of the Escazú foothills. The wind cooled as we climbed slowly into the clouds.

On the opposite hillside I saw uniform, green plants growing in plots the way I’d seen grapes grow on certain slopes in France and Spain. “Is that coffee?”

“Si,” Jim said.

“What are those other trees?”

Between the coffee trees every several feet were large fronds that appeared to sprout not from a trunk but somewhere invisible.

“Plátanos.”

A Brittanica entry says that plantains account for about 85 percent of all banana cultivation worldwide. The next morning, the good cooks at the house would saute them for our breakfast.

The rainy season in Costa Rica begins in April and runs through November. Hence our arrival in late January. The thermometer would make 80 Fahrenheit before the sun dipped over the mountain. By then, the sheets would be turned back on our beds in the cabana behind the main house. I closed my eyes and saw birds of paradise, orange and purple like high-school basketball uniforms.

It was my first trip beyond the lip of the cup.

Hanging next to a dart board was a framed coffee sack: Hacienda La Minita … Cafe de Costa Rica. The sacks are woven from the fibers of the sisal plant, a kind of agave. In addition to the plantains, we ate ripe melon, papaya and pineapple, piña in Spanish but ananas in French—bananas minus the b.

The only good coffee I drank in Costa Rica was the Nicaraguan java and the caturra we’re selling as El Chele, both products of Nueva Segovia from one of Brian’s recent excursions. The man takes his coffee with him, like Johnny and his bag of apples. Brian is no stranger to La Minita, but strange is its grip on him. I saw him sitting on the porch steps, staring off into the volcanic abyss. He looked up.

“Every time I get around coffee trees I get emotional. Like home. You know?”

Vultures of some sort flew sorties over the steep valley. The banana trees gave me flashbacks of Vietnam War movies. A tall pine, planted a few years before Jim’s arrival, arched its back, bent by years of wind.

“If you get lost, look for that tree,” Jim said. “It’s our beacon. Try not to get lost.”

As with the lobsters of Scotland, all the good Costa Rican goes to higher-paying markets far from their native place. Even the house coffee reminded me nothing of the La Minita of far and recent memory.

My first taste of this famous Costa Rican dates to the late-Eighties, I can’t recall where. Brian says that Mecca—then in Brookside, now across from the Whole Foods—carried La Minita. I read somewhere that Bill McAlpin, who started the farm, drove his van up and down the east coast looking for a niche in the nascent single-origin market. Until then, it was all Bourbon Santos and mock-Kona, and dark beans spritzed with nut oils.

It’s easily the first single origin I knew by name. And now here I was, at origin, as they say.

“Try it,” Jim said. “It tastes sweet.”

In spite of the oranges growing all around, we drank orange juice from a jug. Still, I couldn’t resist yanking them from the tree. Every bite: sour! One scraped the enamel off my teeth and kicked me in the stomach. But Jim was not talking about sour oranges.

As with almonds, it’s the seed we’re interested in with coffee, not the fruit. That said, the cherry-red husk and pulp encasing the coffee seed tastes not at all unpleasant. I mean, don’t go eating a bowl of them.

Beneath the skin is the pulp. Squeeze a ripe one and out pop the cleaved twins (out of a particularly large cherry, I found four) of a seed. Surrounding the seed is the mucilage, parchment and silver skin, in that order from the outside in. The seed is the only thing to go into the roaster.

But first it has to be washed and dried, sorted and selected, bagged and tagged. In all, eight weeks from picking to packing. Picking on the side of a mountain is hard work, I can now attest, after spilling the beans.

“For years I couldn’t convince them to put their coffee in GrainPro,” Brian said, wiping parchment off his sleeve. GrainPro bags offer another protective layer. Skin, pulp, mucilage, parchment, silver skin, GrainPro, seed.

The mill at La Minita sits on the banks of the Tarrazu and uses its water in production, a continuous loop through which coffee, in all its incarnations, tumbles, spins and soaks. Eight weeks. Like Germans on vacation.

They were in the middle of the summer, a time of sun and fresh fruit and mostly empty coffee trees. In a couple of months, the tides would shift and bring rain that will soak the place until November. Then, bring on the zipliners.

We all piled back into the tall-sided truck and headed back up the hill. Dogs woke up from their naps to snap at beer-weary baristas from Bend and Portland and Lubbock. Along the way we passed real coffee pickers sorting their fruit by the side of the road. Actually, kind of in the road. They spread their cherries on wide cloths to sort them, green from red from deep purple.

“Somebody’s color blind,” Jim said, studying the fruit in my own basket. “It’s not your fault.”

Only women sort the final product, shoving the seeds into keepers and duds by size, shape and mostly color, because women tend to see color better than men. It’s tedious work, to this guy anyway.

Consider this: When you drink a cup of La Minita, you drink better coffee than the people at Hacienda La Minita drink. The beauty is in the balance: As with ballerinas, so with La Minita. Remember that next time you pull a bag from the merch wall or place a half-full cup in the bus tub. Easy to take for granted, as Huxley said in the latest episode of DoubleShot Folk.

Costa Rica, “rich coast,” is one of the few nations to exist without a standing army. That’s one way to measure rich.

- Mark Brown

Cascara

Coffee, like many of the things we adore and elevate, is steeped in a healthy dose of lore. I read somewhere several years (and many cups) ago that Saladin, sultan of Egypt and Syria, drank a wine fermented of coffee cherries. My logical side wants to assume that this beverage - if it in fact existed, at least in the form I’m thinking - predated the drink we know as coffee, the latter requiring the roasting, grinding and brewing of the seed (“bean”) within the cherry, the latter requiring merely water and a bucket to soak it in. (No easy thing in the Levant of Saladin’s rule, but easier than making a pourover.)

Still, you have to admire the man. It was, if nothing else, an admirable use of a byproduct.

Coffee cherries tend toward red and yellow. We’re now roasting a pink one (the Maracay Bourbon, holiday coffee numero uno). That is, we’re roasting the seed inside the cherry. The cherries seldom make it to the DoubleShot. During processing, they’re soaked (or dried) and pulped before being tossed or used for compost, the role they play in coffee having been expired.

Some of the cherries of Montelín, the farm of Juan Ramon Diaz, do make it to town, in the form of a mystery called cascara. Let’s start with how to say it: not like mascara; more like, ca-SCAR-a. What is it? The cherries I wrote of above have skins that, after they dry, become husks. Bits and piece of those husks, when brewed, become a kind of … something.

Tea, some might say. But tea is typically plant leaves, dried and rolled, then fermented. (Or at least, shrunken.) Cascara is not leaves. Can it be tea?

And, finally, why should you drink it?

I’ve had a hard time defining the flavor. The descriptors that tend to dominate the websites are “rose hip, hibiscus, cherry, red current (sic), mango or even tobacco.” What I taste is almost akin to an exotic fruit juice before it’s sweetened for mass-market consumption. Diluted apple juice comes to mind. Tea-like, I might add, in that the flavor profile is as often as not in the nose.

It’s an interesting choice for those who want to sample coffee in all its forms. Same as a cool backpack or pair of sneaks, it’s a sign of connoisseurship. You should deserve some credibility for drinking cascara by choice.

That said, they were messing around the other day behind the bar when Huxley handed me a cascara nitro. While the creamy top faded fast, the body was fruity, malty and delicious. It was my favorite incarnation of cascara yet.

Overcoming

The first time I met Juan Ramon Diaz, he probably thought I was a maniac. We chatted a bit before cupping a few coffees from their past crop and a few samples I brought from the DoubleShot offerings. There was a bit of bravado in the air, sort of a master-student formality that I’m not a fan of. We slurped and spit our way around the table, and I found myself bored, underwhelmed, and more than a little concerned about the coffees I was attempting to purchase from these young producers. I went and sat outside in the dark on a plastic chair, wishing I were in the woods, enjoying a few moments of solitude. The Nicaraguan farmers took their time analyzing each sample, asking each other why their coffees tasted so good and mine tasted so bad. To say I was offended would probably be appropriate here, and frankly I’ve developed a pretty good palate for cupping coffees over the past twenty plus years, so listening to people make nonsensical comments that don’t jive with my reality can be tiresome. Juan Ramon remained on the fringes of this charade, and I watched him with curiosity. I eyed all of them with a fair amount of skepticism and considerable concern because their coffees weren’t great, but even more because they didn’t seem to know it.

A couple days later, we all met at a nice house on the outskirts of town, where we drank beer and ate an abundance of grilled meat. Sitting out on the patio, the group of farmers I’d cupped with wanted to know how much coffee I could buy, how much I could pay, what type of coffee I was looking for, and how all this would benefit them. I did my best to explain to them that I wasn’t going to offer a price for the coffees based on quality or cupping score; but that I’d only buy the coffees if they were really good. (In other words, a lot of roasters will buy lower-scoring coffees for a lower price, and I had no intention of buying the coffee at all if it didn’t surpass my expectations.) Samuel, most adamantly, wanted to know that I would still be there for them if they had a bad year, and that he didn’t just want a buyer, he wanted a relationship with a roaster. They didn’t just want to dance, they wanted to go steady. The conversation got pretty lively and I may have raised my voice a few times, emphatic that this relationship would only work if they pulled their weight and put some very good coffees on the cupping table. Juan Ramon sat quietly listening, and I asked him what he thought. He told me he was just talking it all in. I told him I’m just like him, normally listening rather than talking. They all laughed in disbelief.

Six months later I was back in Nueva Segovia. A couple of the producers I’d met drove all the way across the country to pick me up at the Managua airport and take me back to the northern mountains where their coffee farms soared high above the distant communities. We got straight down to business the next day, meeting at Juan Ramon’s house to cup the coffees these guys had worked hard to produce. I could feel the heaviness in the room from the passing of Juan Ramon’s father, overlaid with anticipation as we prepared for my final and ultimate judgment of each of their coffees. It’s serious and important, and the environment can be charged with the gravity of my imminent opinions and decisions. I cupped fourteen coffees in all: three from a young guy named Norman, three from my friend Sergio, a few one-offs, three coffees from Juan Ramon, and two from Samuel. I made some calculated decisions about which coffees I was interested in buying, and we talked about my tasting notes as they revealed what each lot was.

From here, it’s a matter of discerning how many pounds each lot comprises and then negotiating a deal with each producer. So here’s how it went down. Samuel had two coffees on the table, but he really only wanted to sell me the one I didn’t like. The good one he was hoping to sell at the Cup of Excellence auction. This guy who was insistent I make a long-term commitment withheld his best coffee and put it out there on coffee tinder (and he did place fifth in the competition, earning him $17.30 per pound and a dance with a large Japanese food and beverage company). Sergio and I made a deal in the car, and then I made the same deal with Juan Ramon. Norman managed to sell me the most coffee of anyone, surprisingly.

Months passed and we finally managed to import the coffees. I cupped each one again, in my office this time. And Juan Ramon’s Java Natural won the day, a real cup of excellence.

I must say that I’m really impressed with these guys. They’re learning how to produce specialty coffee in today’s environment. Things are changing at an accelerated pace. Think about this. According to Mark Pendergrast, coffee cultivation in Nicaragua began in the last few decades of the 19th century, when German immigrants took up the trade. From that point forward, coffee was basically produced in the same way, neighbors teaching neighbors, and any adaptations were generally because small producers couldn’t afford to do things the “right” way. Nothing really changed from a quality perspective because producers were solely concerned with quantities produced. Cup of Excellence first came to Nicaragua in 2002, and likely spurred farmers to put some effort toward quality, but for around one hundred and forty years, production methods were basically static. And then suddenly, over the past ten years there has been an upheaval of that system. Young producers don’t want to just sell commodity coffee, they want to do something meaningful. They’re learning more and more about coffee production, varieties, and processing methods, and they’re experimenting with small lots. The more they know and the more they are connected with roasters like me and consumers like you, the more zealous they are to keep iterating and improving.

Mark Brown and I have been cohosting the AA Cafe podcast for several years now, and traditionally in the last episode of the year we each do a “ten things” list. This year we decided to do “simple pleasures” as our theme. And as I got to thinking about what that actually means – both simple and pleasurable – I thought of one thing that probably should be at the top of my list. No, not a really good cup of coffee (though that’s on my list). It’s seeing people overcome. Seeing people get through tough challenges or prevail against the odds. It gives me a deep sense of pleasure even when I’m not involved in the situation.

It’s striking to me that I asked four young coffee farmers in October to produce excellent naturals for me to cup in April, and they took up the challenge, changed and learned and came through with really nice coffees.

Simple pleasure? Watching Juan Ramon, the introvert, listen to me bloviate about coffee quality and relations with farmers. Seeing Juan Ramon a couple days after his father died suddenly, standing up and being a leader for the family, seeing this project through, and being a kind host to me during an extremely difficult time. Cupping Juan Ramon’s coffee and tasting the care he put into its cultivation and processing. Designing the packaging for the Montelin Java Natural, roasting the coffee, and putting it on the shelf for you to buy and enjoy.

Maybe it’s not so simple. But it is extremely pleasurable.

Superkop: The Timeless Manual Espresso Tool

Out of the “lower lands,” the Netherlands to be exact, comes a unique manual espresso machine called the Superkop.

This tool that’s gained notoriety in Asia and Europe is beginning to get noticed in the American coffee industry. Manual espresso machines aren’t new to the coffee world, but the Superkop is different. “The Superkop steps into this market with a strong design aesthetic, albeit more industrial than art nouveau but striking nonetheless, and a clever way around the pressure problem,” says Scott Gilbertson from WIRED Magazine in his review of the up-and-coming tool.

The Superkop has since been reviewed by Barista Magazine, Mark Prince with CoffeeGeek, and was named one of The Top 200 Inventions of 2023 by TIME Magazine

The Superkop comes in three different colors: red, black, and white. Not only does the Superkop cover just 1 foot by 1 foot of counter space, owners also have the option to wall-mount the espresso tool to save space. Customers are mounting their Superkop in their kitchen, their RVs and their vans for travel purposes.

Included with the tool is a sturdy, wooden base with drip tray, the espresso tool itself along with the lever, a standard size portafilter, and water cup. All you need to make a velvety espresso is hot water and arm strength. Simply dial in your DoubleShot Ambergris Espresso Blend, tamp, add hot water to the water cup, place the cup on top of the portafilter, and attach the portafilter to the Superkop. Once attached, slowly pull down on the lever six times to pull your morning espresso.

“It uses a ratcheting mechanism in the handle to keep the pressure constant as you raise and lower the pump arm,” says WIRED’s Gilbertson. “At the same time, you do have some control over how much pressure is applied. You can regulate the pressure by the speed of your pumping, and this, combined with the volume of beans and how finely you grind them, are the tools you have to control the finished result.”

Clean up is simple. Knock the puck out of your portafilter, rinse the basket and water cup, and reassemble.

Timeless would be the word to best describe this tool. The ease of use of this espresso tool combined with its sleek and simple design is a no brainer for coffee lovers here in the states and across the world. This is a tool you will buy once and have for life. A tool that guests will continue to inquire about at your dinner parties. A tool you will take with you wherever you go. It’s durable, easy to repair, lightweight, and has a small footprint.

Still not sure? Mark Prince, who has reviewed hundreds of coffee products on his prosumer site, CoffeeGeek.com says, "The Superkop won’t be boxed up and stored away. It’s going to stay on the wall, and get frequent use. Should my partner and I sell our house and buy a new home one day, one of the many deciding factors will be 'does this house have a suitable spot for me to mount the Superkop?.' That’s just about the highest praise I can give a product."

Buy yours at DoubleShotCoffee.com.

Kickstarter Q&A

You already made your $10,000 goal, so what are you going to do with the extra money?

We made our goal but the cost to publish is still looming out there, and we’re hoping to reach our initial internal goal of $25,000. If we have any extra money after publishing, we will use it to promote the book. You’re investing in this book’s existence and getting one of the first copies to be printed. We really hope that this will be an outstanding work both visually and informationally; a collection of stories that will make you laugh, warm your heart, and take you on the amazing journey I’ve lived through the DoubleShot over the past twenty-plus years. The book is not an end in itself; it’s the beginning of something new that we hope will launch the next phase of an even bigger career in coffee. That’s why we want you to be a part of this new venture right from the beginning.

Do I need to go through Kickstarter or can I just give you cash?

A few people have given me money outside of kickstarter, which is great because we get to use all the money instead of giving some of it to Kickstarter. The benefit to us in getting more Kickstarter pledges is seeing the community rally around the project collectively. It gives us a platform to demonstrate our success and clout online so that future projects can begin with more ease once we have a proven track record. But we will happily and gratefully accept your pledges any way you want to give.

Is Kickstarter the only way to get the book or will I be able to buy it later?

Yes, you will be able to purchase the book once it’s published, even if you don’t back the Kickstarter campaign. We launched the campaign in order to get a head start with financing, to make sure there was a general interest in the book, and to have a basic understanding of how many books we’d need to print initially. Once the Kickstarter campaign ends, we will begin “pre-selling” the book at purist.coffee. The price of the book after Kickstarter during pre-sales will be $50. The downside of waiting is that you won’t be eligible for some of the rewards we’re offering on Kickstarter, like the Contrasting Coffee Collection or the cupping course. The Collector’s Edition will be available for pre-purchase for a limited time after Kickstarter ends.

You ever think of doing a coffee table book about coffee?

Ha. Funny you should ask. This is going to be a substantial book. It’s hardcover 10x10 inches. That’s nearly a square foot. If it’s not on your coffee table, it will take up quite a bit of space on your bookshelf.

This GoFundMe thing doesn’t seem like the DoubleShot’s M.O. Why not just publish the book and then sell it?

We purposely chose to fund the book project on Kickstarter instead of a platform like GoFundMe because we’re not asking for a hand-out. We wanted to make sure this was a viable project that people wanted, and if it proved not to be, we wouldn’t take any money from backers. That’s how Kickstarter works. You either make your goal or you don’t get any money. Though we’re not allowed to say that we are “selling” anything on Kickstarter, we priced the rewards at what we would sell each book or bundle in our retail store. So you’re not “buying” anything through Kickstarter, but the amount we’re asking you to give is commensurate with the value of what you’re going to get as a reward.

What do you make of the fact that you’ve more than doubled your initial Kickstarter goal?

We were actually really surprised how fast we made our goal and how much people have given to the project, and it’s made us even more excited about getting this book out into the world. I know that this immense amount of support comes from a broad group of individuals who have, over the years, become fans of DoubleShot and what we do. People who have been rallying for us for years, championing our cause by showing up and by purchasing our products and consuming them thoughtfully. The outpouring of, not just money, but verbal affirmations from this community throughout the campaign has been touching and motivating, and I feel a huge debt of gratitude to everyone who has contributed and encouraged us over the past sixty days.

I’ve learned so much, even over the course of writing, discussing and thinking about the book, and speaking to groups because of the book. It’s honestly taken me to another level of understanding what it means to truly live, and how I managed to get away with all the things that brought me to this point in life. I honestly think I have something important to say through this book. There’s nothing monumental in my head that you probably haven’t thought about before, but maybe I’ll show you a different way. I’ll nudge you to change, just a tiny bit. Stories are the only thing that separates a bland, generic existence from an authentic, meaningful life. If you don’t know the story behind a thing, you’re just a blind consumer. I hope to tell the story of coffee. To give you enough information that your eyes will be opened and the next cup of coffee you drink will taste different because of what you know.

A Bean Apart

Rancho Gordo beans, like DoubleShot coffee beans, come in one-pound bags from various regions. I guess the question is, Why shouldn’t dried beans be a craft product?

I’d been searching my six or so grocery stores high and low for something other than black and pinto. Anasazi got my attention, and I found a bag of cranberry (what the Italians call borlotti) in some aisle or other. Surely they were out there, somewhere.

“The pumpkin lover is a lonely connoisseur,” William Woys Weaver once wrote, noting that pumpkins were merely squashes and the varieties were boundless, in the hundreds, versus the one jack o’ lantern orange. I sang the same sad lament over a pot of beans.

But no more. Thanks to Rancho Gordo, my bean larder is brimming. This Napa Valley-based purveyor has been offering dried heirloom bean varieties since 2001. Through its Xoxoc project, it helps small farmers in Mexico get their indigenous crops to market in spite of the bureaucracy that “discourages genetic diversity and local food traditions.”

King City pink. Tarbais white, Domingo rojo, Chiapas black … and we’re just getting started. Rancho Gordo beans are so fresh they often start sprouting during even a short soak (I opt not to soak, relying on Steve “Gordo” Sando’s own cooking method, which never fails). These are heirloom beans, so supplies are not unlimited (they have what they call “waitlist beans”).

You’ve probably noticed these beans in our market. If you’ve not bought a bag, I suggest starting where your eye draws you. Among my faves now are the Royal Corona and Ayocote Morado. Creamy, firm and velvety-rich, they smear wonderfully on a thick, warm tortilla.

- 1

- 2