Roastmaster's Blog

A New Theory of Relativity

When I was ten years old, I designed a mansion. It was really more of a castle, but when I took drafting class in high school, I fleshed it out into my dream home — something akin to the mythical Wayne Manor.

I was born with an affliction: a poor kid with expensive taste. I remember, at around thirteen years old, going on a shopping trip to the mall with my mom to buy a pair of khaki pants. I found a pair that I loved, but they were way out of our price range. So we spent the rest of the day going from one department store to the next trying on less-expensive khakis that I’m sure were perfectly fine. But I’d already made up my mind. And apparently I was a brat.

After I started my first company out of college and transitioned from football to adventure sports, I decided I needed a four-wheel drive SUV. So I hightailed it to the Land Rover dealership to purchase the safari vehicle of my youthful dreams. During the two years I spent out west before returning to Tulsa to open DoubleShot, I basically lived out of that Discovery. I saw some amazing places and learned to live a simple life, but I still harbored the dream of being rich. And famous. My business plan boldly forecasted rapidly escalating sales, following a path I predicted in my early-20s: that I would be a millionaire by age 33.

From 2004-2007, I lived very primitively. And by the end of my thirty-third year of existence, despite expectations for my life’s fortune, I was destitute. I’d grown intimate with poverty, dodging debt collectors and the repo man. Still to this day, my fight-or-flight instinct kicks in whenever my phone rings. But I’ve subsisted by escaping into the wilderness or a good book, making things instead of buying them, self-reliant in all things, finding pleasure in simplicity and nuance.

I spent a couple of years peering into that other world. My girlfriend at the tail end of my 30s lived in a mansion, took airlines instead of long drives, and opted for luxury accommodations in her travels. She didn’t think twice about dining at expensive restaurants and could easily afford extravagances I’d only dreamed of. I’d learned it was difficult to be happy when you can’t pay the bills. But during that period of my life, I discovered that satisfaction comes from earning, and there’s more delight to be found in small luxuries than extravagant ones.

I can spend hours in a creek bed picking up rocks. Sit in front of that wonderful Moran at Gilcrease staring off into a painted landscape that takes my imagination on a meandering journey to a place of freedom and serenity. I cherish a good book more than a night on the town. And an amazing cup of coffee … I wouldn’t trade it for the best wine in the world.

“Affordable luxuries,” we call those. Even the most expensive coffees we’ve ever sold don’t hold a candle to the price (per milliliter) of many folks’ everyday wine. We have an idea of what coffee should cost and it’s not the same as our idea of what things like wine should cost. Wine almost always comes in the same size bottle, so at least you can compare one to another. Coffee bags have gotten smaller, with most companies selling 12-ounce bags or the new trend of 10 ounces, usually for the price of our 16-ounce bag of coffee, if not more

Oftentimes when I drink wine, I think all winemakers must’ve gone to the same school. It’s like that in coffee too, but our school sucks. Roasters tend to be baristas who got promoted (like a bartender being promoted to vintner) or business owners who got the automated system (I don’t know if there are wine-making machines that you can dump grapes into and then let the computer do the rest). Roast profiles all copy each other, probably letting AI do the job, and produce a bunch of coffee that might taste good to some judge at a Coffee Quality Institute event but doesn’t taste good to me.

It’s a tough business, I’ve learned. Now, I’m not in it for riches. I gave up that dream a long time ago. I don’t want a boat or a membership at the country club. You don’t have to worry; I won’t show up at your cocktail party. (I wouldn’t even have anything to wear.) No, I do this for an entirely different reason. I do it because I actually love coffee and everything it stands for.

But let’s take a step back.

Coffee grounds are simply smashed-up coffee beans, which are the roasted seeds of coffee cherries. They grow on trees in the tropics, and the best ones are at high elevation on mountainsides in places like Boquete, Panama and Yirgacheffe, Ethiopia. It’s even grown inland from some of your favorite tourist destinations in Mexico and Costa Rica.

Until global warming creeps up into the Rockies, we’re probably going to have to continue buying coffee from the tropics. Except for Hawaii, the United States is not in the tropics. So, apart from over-hyped Kona blends, we aren’t able to grow our own coffee. I travel to places like Colombia, Nicaragua, and India in order to get to know the land and the people who are responsible for the broad range of coffees I roast. Like the people who grow the coffees, each one has unique characteristics, bringing the aromatics from these exotic origins to your morning cup.

You probably don’t pay any attention to the commodity markets. Or tax rates. When a vote comes around for a third-penny sales tax, you probably don’t even know or care what a third-penny is. So I certainly wouldn’t be surprised to learn that you don’t know what tariffs really are, and you might even think the US government is levying these taxes against other nations.

Maybe you like the idea of tariffs. Maybe you think we can bring manufacturing back to the US if we make imported goods really expensive. Everything you see at Walmart could be produced in our nation's factories, built by American hands. Perhaps you’d like to have a job on an assembly line. Probably pays pretty well, right? Maybe then we can isolate ourselves from the rest of the world and create a homogenous society like the pilgrims always dreamed of.

Tariffs are taxes charged to people in the United States who import goods from other countries. I pay tariffs when I import coffee from producing countries. I’m paying tariffs on The Coffee Purist book, which is being produced in China. When I buy coffee from other importers, they pay the tariffs. But guess what. That increases the cost per pound, so they charge me and I charge you. Trickle-down economics, Reagan might call it. We haven’t felt the full impact of tariffs yet because we’re all still selling through pre-tariff inventory, but little by little it’s creeping in and you’re going to take it on the jaw.

While the commodity market (a financial market that speculates in oil, minerals, agriculture products, etc.) plays a large role in the price of commercial coffee (think big brands like Folgers, Maxwell House, Starbucks, etc.), those traders only occasionally provide a base for differentials in higher-end specialty coffees like mine. I happen to be friends with most of the producers I buy from, so I pay them more-or-less what they ask, which is often double what the commercial market is paying. As the commodity market has risen over the past year, the high price of commercial coffee has driven up the costs of these big brands, and the rising tide lifts all the boats. Thank goodness alcohol consumption is on the decline. Perhaps we’ll collectively have the budget to spend more on coffee. (See graphic.)

But beware. Do your research and you’ll find that nearly every coffee roaster in the US claims to have relationships with the folks who produce their coffee. I’m not sure if everyone is simply using the same AI bot to write the “about us” section on their website, or if they lack the integrity to tell you the truth about their “ethical” sourcing. But very few have actually been to the places where their coffee is grown and even fewer know the people who grow it. If they did, they certainly wouldn’t hide behind names like “Southern Weather” or “Monarch.” Perhaps they would write the name of the producer on the bag. Or some other foreign word that causes you to try and pronounce it in your head over and over again, e.g. Lah Mee Nee Tuh, Bam Bee Toh, Moan Tay Leen, etc. (Those are farm names.)

With escalating prices, due to tariffs and commodity markets, a lot of “specialty coffee” roasters are choosing to buy lower-quality coffee in order to keep their prices in check. That’s an easy thing to do, particularly when you’re not friends with the producers. I could simply call one of the big importers and ask them to send me samples of a few big commercial lots, and even though the coffee wouldn’t taste as good, most consumers are price sensitive and care less about quality than value. If you look around at any coffee shop (mine included), you’ll see that most people are consuming coffee with milk and sugar and flavorings. (We only have chocolate — and even though most people prefer it, ours isn’t chocolate-flavored syrup; it’s actual chocolate). Milk and sugar and flavorings mask the taste of bad coffee. Bad coffee is the result of laziness, ignorance, or prioritizing money over quality. If our “specialty coffee” roasters continue to pay low prices and purchase low quality coffee for their production roasts, blending to hide the defects and the farmers, the small producers around the world who are trying to elevate their craft will have no incentive to continue striving for quality. And that will be a HUGE loss.

I do my best to honor the farms where the coffee comes from and the people who work hard to produce the coffees. I’ve tried like hell to develop relationships with people around the world who I trust to produce excellent coffee and who believe in the same ethics of quality, hard work, and integrity. I love the craft that coffee can be — using our hands to care for the coffee plants on the farm and to pick the coffee cherries off the trees when they are ripe. To feel the coffee on the drying bed or the fermentation tank to determine its readiness. Hand-sorting coffee beans for quality, removing those beans that might taint our delicious brew. Even loading the coffee into bags at the mill and carrying those bags on men’s shoulders to load into a truck or container. My hands turn knobs and push levers, pulling the trier to see how the coffee is progressing through the roast. I roast by hand and I use my fingers to comb the quakers out of the cooling bin as it spreads hot beans over a high-speed fan. I love a good hand-made pourover. It’s the way Juan Ramon makes me coffee when I’m at his farm (Montelin) in Mosonte, Nicaragua. That’s how I make my coffee every morning when I wake up, even using a hand grinder instead of electric. It’s the manual nature of it all that draws me to it. I’m blue collar through and through. But I have expensive taste.

When people tell me they don’t like coffee, I say I don’t either. Because I can guarantee that the same coffee they didn’t like, I also don’t like. I’m not sure where a good price point would be for that commodity coffee. I suspect most producers are breaking even around $2 per pound, so for sustainability’s sake, it must be higher than that. But with the commodity market fluctuating around $4, it’s pushed specialty coffee prices into new territory. Specialty coffee is not commercial coffee. We are not Starbucks or Folgers. So what is the right price for specialty coffee? Right now, I’m paying a huge range of prices for coffee. Frankly, the cost of living is different everywhere I go. That’s part of the reason Hawaiian coffees are so expensive and Vietnamese coffees are so cheap. Living in Panama is not the same as living in Nicaragua. Hell, I could live like a king in Bolivia. So each producer asks me for a different price. I want them all to be successful and continue improving their quality each year. So I pay it. Do I think specialty coffee prices are too high right now? No, I think we’re used to paying too little. We all need to get accustomed to the idea that inexpensive coffee is not good coffee.

We have no way of knowing what’s happening on the local level for coffee producers, but I can tell you that exporters and cooperatives have power over small producers. So even when you see the C-market soaring, that may not trickle down to the farm level. When you buy coffee, whether you like it or not, you’re making an impact by supporting either low quality or high quality, either commercial or specialty. When you support low quality, you’re feeding into a system that doesn’t care about people, only about money. If you care about people, I’d suggest you carefully consider your purchases. (If you’re reading this, ignorance is no longer an excuse.)

Coffee bean prices at DoubleShot are going up. I’m paying more money to producers than I ever have. And since I’m not rich and privy to loopholes in the tariff assessments, we’re going to have to continue paying extortive taxes to the federal government. But I don’t see these prices ever coming down. Even though it pains me to have to charge my customers so much more money for excellent coffee, I’m happy that the farmers are finally making the profit they deserve. Our coffee has gotten better over the years because of access to better beans, acquisition of better equipment, and more experience roasting different types of coffees from all over the world. I’ve just gotten better at it. Better equals more value, and more value costs more money.

It’s still an affordable luxury.

Pictographs and Paint Cans

Nowadays it’s mostly my own madness, but we used to have art shows at DoubleShot. Way back when we were just single-wide, I mounted steel rails high up on the walls that held rods where we hung rotating pieces from local artists. My friend Candice was in charge of contacting artists and scheduling each show. During this time, I learned that many artists spend a lot of time on their works and become very attached, to the point that they put price tags on paintings that almost guarantee they won’t have to part with them.

I’m not like that. If you even considered me to be some sort of artist, I’d say I’m a production artist, at best. I design things that I want people to take home. I create pieces that are temporary and curious. My work isn’t supposed to be perfect, just interesting. I took a page out of Shepard Fairey’s book (of which I have a few) when it comes to posters. I started noticing his OBEY signs around Nashville when I was visiting friends there in 2003. I read Shepard’s manifesto. And I brought that ethos into the DoubleShot when I started creating my own works. It’s about asking questions. It’s about piquing curiosity. We want our customers to ask questions so that we can share what we know and what we do. So if you ever see something in the DoubleShot and ask yourself, “I wonder what that’s supposed to mean?” I did my job. Now go ask a barista.

Art is subjective. Even the definition of art is subjective. Mark showed me that some guy duct taped a banana to the wall and a collector bought it for some ungodly price. Methinks Scotch tape and a coffee bean could be next. But I remember once when a show went up on those 18th & Boston walls, I puzzled at the art and told Candice, “I could’ve done that.” To which she replied, “But you didn’t.” And that’s the rift. Some art is fantastical. Some art is simple. And just because you feel it’s beneath you doesn’t mean it isn’t art.

People just like us (only way tougher and more capable) scratched stick figures of people and longhorn sheep, bears, boats, snakes, and all sorts of things into rock walls thousands of years ago. Sometimes they used ochre and other times they tapped the rock in paleo pointillism like Seurat’s ancient ancestors. Today we put ropes and stanchions around these images to protect them from being defaced by bored teenagers, and park rangers lead interpretive talks about the people who lived and made art and died in these places.

To some, the geology of the walls is interesting enough, but to most of us it’s the art on those walls that draws our attention. Were the paleoindians defacing the cliff walls by making petroglyphs and pictographs up and down the desert corridors? Some primitive form of graffiti? Perhaps they were, but now we protect it as if it’s a Banksy stencil on a London flat.

If you look at the definition of graffiti on the internet, it’s defined as a form of vandalism, which is “willful or malicious destruction or defacement of public or private property.” But graffiti artists aren’t painting in order to cause harm to someone, and in my opinion they aren’t “spoiling the appearance” of austere, grey concrete walls or decrepit, decomposing factory facades. A lot of these guys are really talented and invest a significant amount of time and money for specialized spray paint to decorate the undersides of our infrastructure. You may not like it because you can’t read it, and when you can, you don’t like what it says. You’re confused by Rebop, Mango, Swank Tabu and the like. And you don’t like being confused. Because, just like Shepard Fairey’s OBEY posters, you might have to actually think and consider the fact that mega-corporations are bombarding you with words and symbols every day in public spaces trying to entice gratuitous consumerism. Words like Nike and Pepsi and those ubiquitous golden arches are so prevalent that you barely even think about it any more; they’ve bored deep into your subconscious.

I’ve never been a big fan of paid advertising. It seems like a promotion lacking creativity when there are so many ways of getting your message out for free. Way back in the early 2000s, I’d put DoubleShot stickers in places they might not necessarily belong. And then a customer named Jonathan showed me how to cut stencils into corrugated cardboard with an X-ACTO knife. So I started spray painting the sides of empty Solo cup cartons with the word COFFEE and some with a primitive-looking DoubleShot logo, and zip tying them to telephone poles up and down Riverside Drive. People would see a sticker at, say, Turkey Mountain and then follow my kraft blazes down the river to our front door for coffee. Once, a city worker came to DoubleShot with a big stack of my cardboard signs and told me it was against the law to put them on city poles. I was thankful that he returned them, comped him a cup of coffee, and promptly went back out to zip tie them on poles that our governors have no authority over. Then I discovered the stencil burner and mylar plastic sheeting.

If you’ve been around long enough, you’ll remember that most of the DoubleShot tshirts, hoodies, and trucker hats from the early years were painted by my dad and me with stencils I cut in plastic. We had a lot of fun airbrushing multi-layered stencils, and the designs were only limited by our imaginations.

My dad and I started restoring vintage cruisers and I created a new company called Native Bikes. We would disassemble each one and fix whatever might be wrong, sandblast the frame, and I would dream up a theme and paint scheme, oftentimes using stencils for flames, names, and patterns. The logo I’d created for Native was cut into an aluminum head badge, which branded the front of every one of our bikes, including my own racing bike.

I took that Native moniker with me on many mountain bike journeys. We painted my bike frame a metallic grey and baby blue with flames on the top and down tubes, and I named it nemesis. That bike and I felt like the nemesis of many cyclists, and our go-anywhere approach made us the antagonist to customs, regulations, and laws across the American West. The name stuck, and when I took to the streets with stencils in hand, it felt only natural to bring it with me. But I’m a minor figure (even a non-entity) when it comes to art.

I did attend a liberal arts college, where I was required to take an art participation and an art appreciation course. So I chose hand built clay (which found me crafting slab bowls and animated statues) and “Classical Gods and Heroes” (which introduced me to The Odyssey and all manner of other Greek mythological characters). In most forms of art, I’m better at appreciation than I am at participation. So I admire the 3,000 year old rock art in the Colorado river valley outside Moab. I appreciate the genius of renaissance painters whose work dangles on museum walls. I gawk at massive, corpulent black statues in Botero Plaza in Medellin. And I marvel enviously at the skill of people with aerosol paint cans who create whimsical, colorful, intricate designs in the nooks and crannies of public spaces, most of which you wouldn’t dare to go.

Like the Hindu rangoli designs on the doorsteps of homes I visited in India, street art is temporary. Government employees and citizen vigilantes are constantly blocking those colorful concrete paintings in drab grey and brown overcoats. I admire the art until it disappears, and then I wait for creatives to redecorate on some moonlit night. Like discreet billboards, our street artists are painting their tags in places you might have to look for. Oftentimes they won’t block out your view of the countryside, but peek out from the buttress of an overpass. That’s the way I like it. Art only found by the curious and observant.

And since I love free advertising, I’ve taken this opportunity to borrow my favorite Tulsa tag for a new line of products. Fittingly, this comes from my other company, Native Design, through an off-color project I call nemesis.

Over the years, I’ve ripped off some of the best. Shephard Fairey, Banksy, the paleoindians, Maurizio Cattelan, Johannes Vermeer, Bob Bernstein, Rube Goldberg, Magritte, Gainsborough, Vettriano, Picasso… Boost.

I am the nemesis, after all.

Coffee in one hand and candy in the other

Times have changed. I’ve fought it, and mostly lost.

I am afflicted with a resilience and steadiness that throws most people off. But it comes with a downside. I have ideals that I chase, doggedly believing I’m going to change the world. And the world largely ignores me. Inside, I feel calm and uncompromising until I don’t. Then a figurative storm erupts inside and the acid rain of crushed hope pours down, washing away my dreams until I resign to no longer care. Because sometimes I feel like not many people in the world do care. And sometimes I wish I didn’t.

Yesterday was one of those days. It was all over my face, because I wear my heart on my sleeves. I was a bear, impossible to mollify. I barked and snarled and growled. I looked around for problems I knew I couldn’t untangle. I thought about issues I’ve tried to fix for years with no success. I resolved that I’d stop giving a damn, stop noticing, stop expecting. But the problem is, as a like-minded friend put it, I have high standards and I expect a lot out of myself and others. That’s a problem because I can’t just salve my discouragement by lowering my expectations of those around me; it would require lowering the expectations I have for myself as well.

I don’t have to lower my personal expectations because when it comes to getting shit done, I’m a machine. I could probably out-work my dad, which is no small conjecture. I learn fast and adapt and use tools I’ve developed over the years to ensure I’m doing my best work most of the time. I do not care what it takes to get something done, I will do it. My mantra has long been: “You can’t beat me.” Don’t even try.

So that leaves me in a quandary. I try to give people the tools to achieve excellence, but they don’t like my tools, don’t use my tools. I try to show people a better way, but people don’t want a better way. I remember when I was alive in Boulder Colorado, I looked around at the opportunity to give that community better coffee. They had decent coffee at places like Brewing Market and Peaberry Coffee. But Boulderites preferred the swill served at Trident over on Pearl instead. I knew I could make coffee that was better than anything ever brewed in that town, but eventually I realized Boulder didn’t want better coffee.

And sometimes I wonder that about Tulsa, a less-inspiring place to drink coffee - and maybe that’s precisely the reason we should be drinking better coffee. We don’t have mountains outside our windows to distract our attention. We don’t have world-class athletes rolling in on bicycles to meet up for a cappuccino. (We do, but even the athletes in Oklahoma have to leave in order for us to acknowledge their accomplishments.) We don’t have “cool” to obscure a lack of “good.”

A lot of people come to DoubleShot. Not every day. But the number of people who have been to DoubleShot must be in the hundreds of thousands, if not in seven figures. And in the early days a lot of those people came because the coffee was good, yes, but also because there was something in the air. Not just my air, but all those tall guys wearing tight black t-shirts brought something special too. Most of them came from a conservative Christian upbringing, like me, and I suspect they appreciated being in an environment with passion (a word derived from the suffering of Christ), rules and high standards.

Passion comes from the same Latin root as patience: an attribute my mother warned me not to pray for because God might grant that trait through long-suffering and adversity. But I didn’t need God to pepper my life with tribulation; if there is a path of least resistance, I choose the other. It’s one of the reasons I divorced myself from the church as a young adult. I’d been thinking about what type of person I wanted to become and what it might take to achieve that. I looked around, comparing people’s lives with the resulting character I saw in them, and it seemed clear that hard work and endurance were the keys to building the life I wanted. I saw that the life of ease tends to make people weak, negligent, and unprincipled. And the words I’d heard so many times growing up in church echoed through my head: “Let go and let God.” It’s a New Testament ideal, a far cry from the Old’s trials of Job. I saw that nouveau doctrine playing out in my church, with the faithful beseeching God to do things that only required a little clever rumination and elbow grease. And I knew our differences were irreconcilable. (What would my earthly father have said if I leaned on him to do the things I was too lazy to do myself?)

Around that same time, I was exposed to the ultra-wealthy population of Tulsa when I moved here from rural Illinois to become a personal trainer in Midtown. I couldn’t even begin to comprehend the riches that these people had, and most of them came from generational wealth, compounding the divide between us. They couldn’t comprehend the life I’d come up in or the lifestyle choices I was forced to make. At first I was a little intimidated, because we’re taught that money is power. I wasn’t sure exactly what that meant, but it didn’t take too long for me to realize that sentiment doesn’t hold true in the gym. I flipped the narrative upside-down and made sure my clients understood the power structure when it came to strength and fitness, and I was their master. I’m a generalizer and things were really clicking into place for me as I trained my body and mind with self-imposed hard work, strain, consistently pushing and expanding my limits. You can’t buy that. There’s no easy way to attain the types of traits that I wanted to define my life. This is where I thrive, eschewing the Tim Ferris-style life hacking and lottery-winning shortcuts to “success” in order to just buckle down and engage in good, honest labor. Because whenever you see a rich person who is really fit, they may have had the leisure time to train more than average and they may have had the funds to eat healthier than usual and they may have even hired people to coach them in the right direction. But they still had to put in the work, develop the self-discipline, and do things they may not have wanted to do in order to achieve that goal. I bet that’s hard for a rich person.

But maybe they just had cosmetic surgery. Liposuction. I’ve always wanted to get liposuction. I just need to rid my belly of all the excess fat cells I developed as an Oreo-addicted adolescent and I’m just sure I could have a six pack. But I’m too much of a coward, all the what-ifs and unintended consequences dissuading me. And then there’s the fact that it’s cheating. I nearly cheated in college. Not on exams or in anything academic (unless you consider using my charming personality on my professors, cheating). I nearly cheated in my extracurricular religious pursuit: football.

My hometown friends and I idolized a bodybuilder named Mike O’Hearn, because he claimed to be a “natural” bodybuilder, meaning he didn’t take steroids or growth hormone or any other banned substances. But the guy was massive and ripped. Broad shoulders, huge pecs, six-pack abs, and hulking thighs, he was a statue of manly perfection. We wanted to be him, and the idea that he managed to grace the cover of Muscle & Fitness Magazine through sheer hard work was all I needed to hear. I’m sure there’s a certain amount of genetics involved in the disparity between my body and O’Hearn’s, but I watched other guys in the gym begin to look like him while I continued to look like me. The difference? Those guys were doing ‘roids. I knew there was at least one guy on my college football team doing steroids and I suspected there were several others in the conference who were juicing. We all knew pro cyclists like Lance Armstrong were cheating, baseball players were being found out, and the idea that the massive men playing in the NFL were passing drug tests seemed like a farce.

So I carried $250 cash in my gym bag every day for a couple years. Each day I went to the gym intending to spend the money with some Mike O’Hearn lookalike who would give me the gym candy, take me into the locker room and show me how to inject it into my arm or leg, or maybe it was oral. Hell, I had no idea. But every day I would get to the gym and remind myself that it was cheating. Anyone could take steroids and get jacked. The trick, for me, was building a huge amount of strength, power, size, and speed without cheating. So I never did it.

Those are called principles.

I went to Society on Cherry Street to have a burger for lunch. It’s not the best burger or fries and the service isn’t particularly good, but I’m a man of routine. I don’t like to exacerbate my decision fatigue by trying to decide where to eat. They have a nice patio with a blazing fireplace, and I don’t generally feel sick or bloated after eating there. When I walked in, I recognized a man sitting at my usual table who has been a regular at DoubleShot since the very early days. He was friends with Chicago Bob, who shockingly died in a car accident. I don’t really know this guy, but he’s quietly been around for a very long time. In fact, I’d just seen him at DoubleShot earlier in the day. He was engrossed in conversation and didn’t see me, and I didn’t particularly feel like idle chit-chat anyway. Eventually he left, but came back because he forgot his scarf. And then he happened to noticed me, and came over to my table. He began to tell me that DoubleShot is a really special place. He said my work is understated but the passion that I have seeps out into the customers and creates a “sacred” space. He said that it’s become a “home away from home,” and that it’s meant so much to him and his family for many years.

I knew this guy was solid because of the people he hangs out with, but his words really meant a lot to me, especially with my current state of mind. He won’t have any idea, but everything he said was just what I needed to hear. I almost had tears in my eyes, but he left with his scarf and I stoically finished my burger. Then as I got up to leave, a man at another table called to me and said, “I know who you are.” I walked over to his table and he told me he really loves DoubleShot. He said he drives by every morning on his way to work and stops in every Friday for a treat. He brought his daughter there and now she goes every day. He said it’s really something special and that the coffee is the best in town, maybe anywhere.

I was flabbergasted. I had no idea what to say to either of these guys. I just thanked them and told them I was having a hard day and their words meant a lot. I know that we tend to believe in the supernatural based on unexplained coincidences, and I felt that. It truly seemed like something compelled me to go to Society (as opposed to eating ramen at my desk or Roosevelt’s, my other lunchtime haunt) and that same spirit coerced these two men into saying something to me. The Great Spirit, maybe, which guides me when I’m in the wilderness. Or maybe it was just the random kindness of people.

It buoyed me a bit, and I started to think about all the problems I experience, all the hurdles, all the aloneness I feel. I thought about what that first guy said about my passion creating a sacred space. And I could feel myself centering once again. I think after my mother got sick and stopped working at DoubleShot, I found myself in the midst of so much sudden change and paperwork and in a management crisis. I started focusing on how to fix the problems and took my eye off of the basis of my beliefs. What makes DoubleShot different from every other coffee company out there is our unwavering commitment to operating under a strict set of standards. Beneath those are a list of values and practices that define who we are and what we believe in. Not everyone who comes to DoubleShot will know that it’s this way, but if you hang out long enough, one should feel it.

After lunch, back in the office, I went on a long tirade about our company values. I think what I realized after talking to the two guys at Society is that the people who “get it” are folks who understand that the coffee is really good because of my unwavering commitment to that core set of beliefs. They love the coffee, but they aren’t surprised that it’s good because they know I’m stalwart and resolute. Most people aren’t a part of our tribe. They’ll get mad that we messed up or they’ll disagree with the way we do something and start patronizing another shop that doesn’t know their ass from a hole in the ground. Not enough people buy into the idea of foundational values for a business, but if we don’t start focusing on the importance of those things, this place is going to careen into oblivion and I’m going to let it.

I slept hard and dreamed vividly and woke up feeling like I’ve been trying to maintain the “old way” during a changing culture that has lost sight of what coffee really is and what it means to do things with integrity.

People don’t know how fragile this ecosystem is. I’m still the key man and if I go out in the wilderness and don’t come back or if I give up hope and decide not to continue, the whole DoubleShot experiment is over. Thankfully, there are people like the two men at Society who preserve the integrity of this thing with their appreciation and assurance that I’m not wasting my life. It’s about a lot more than our original mission. Today, our continued existence must revolve around that list of values, practices, and core beliefs.

So here it is:

Craft - hands-on roasting, packaging, design, storytelling

Knowledge - history, science, agriculture, processing, varieties, cultures, equipment, consumer behavior

Integrity - honesty, fairness, reliability

Quality - product, place, intentionality in all

Work Ethic - think about the meaning of those two words

Relationships - with the producers of all our products, our customers, and others in the industry and our community

Proficiency - sourcing, roasting, design, drink-making, and storytelling in the written word, videos and audio production

Conservation - not wasting resources, over-using energy, or throwing away what can be reused

Freshness - not compromising this for a dollar

Health & Fitness - through sport, eating well, encouraging regular exercise and healthy coffee drinks

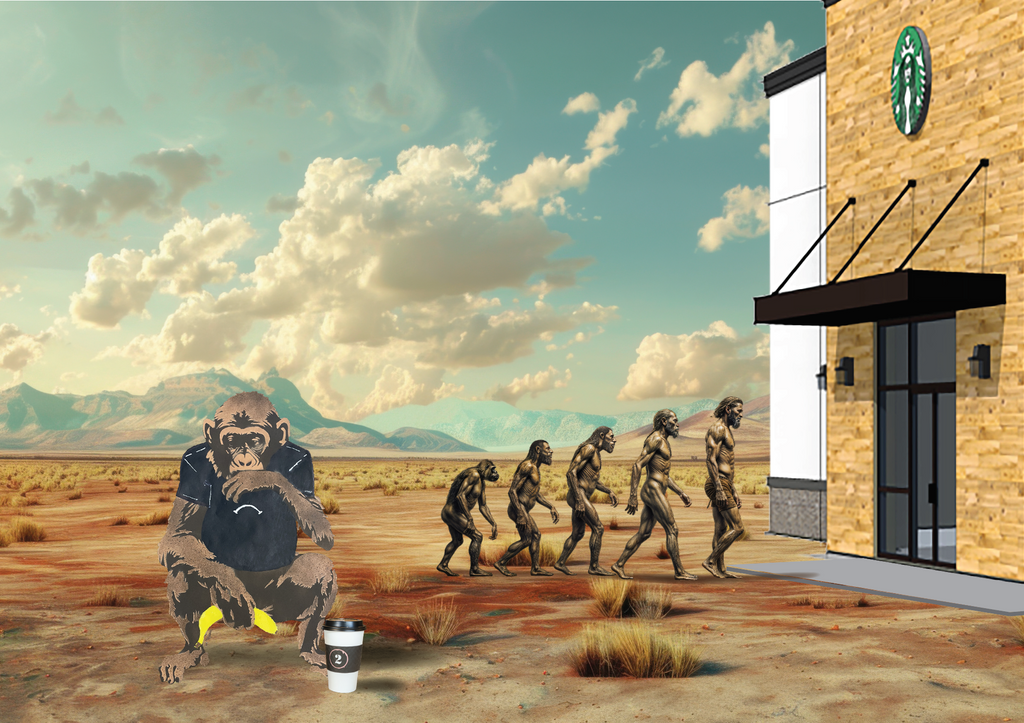

I’m constantly thinking about what makes us different from all the other coffee roasters out there. The big guys like Starbucks and Dutch Bros, to my estimation, have no interest whatsoever in coffee. They are caffeine dealers, at best. They are huge because they scratch the itch of mainstream society. Sugary, caffeinated milkshakes are what most people consider “coffee.” Caffeine is not coffee.

But what about the local roasters that have popped up all over the US over the past few years? That’s good, right? Because, as I learned way back in 1998, freshness is really important when it comes to the taste of coffee. But that was just the first thing I realized when it came to roasting. Since then, I’ve developed a whole arsenal of skills and knowledge that determine whether or not that fresh-roasted coffee will taste good. Most roasters don’t know and don’t take the time or have the curiosity to find out what those factors are. I’m sure you’re not aware of this, but the overwhelming majority of small roasters are roasting the same coffees, maybe calling them something different for the sake of marketing, and don’t have the first clue how to actually roast coffee because their roasting machine is computerized and programmed solely to turn green coffee brown. They don’t have the palate, the interest, or any concern whatsoever about serving you an excellent beverage. They have cute names for their blends though.

How about the heavyweights in the specialty coffee sector? You probably know the names. Well, let’s ask some questions. Why are they selling so many blends instead of focusing on relationships with producers and highlighting single-estate, single-variety coffees? What’s with all the expensive packaging? Why are they selling coffee in 10-ounce packages for prices that you would normally expect from very high-end 16-ounce bags? Why don’t they talk about how they roast coffee? Who is roasting the coffee? Is it a robot, like the robot baristas they showcase?

What about all the fancy brands you see on the grocery store shelves? A lot of those are local. But coffee beans on the grocery store shelf are not fresh. The roasters put “best by” or “expiration” dates on the packaging, generally a year from the time it was roasted. That’s not quality. That’s a money play.

All the hoopla about AI these days is infiltrating everything from decision-making to art to communication. Need a website? AI will design one for you with AI generated images and AI generated text. Want to start a roastery and coffee shop? No doubt, AI will order your coffees, roast them, make the drinks, greet your customers. Everything except cleaning the cafe. You’ll still need to hire immigrants to do that. Is that what you want? Do you want to go to a coffee website and look at fake images and read text composed by a computer?

At DoubleShot, we do everything the hard way. I design all the packaging, and sometimes I even craft the packaging myself, by hand. I travel to places where coffee is grown, so I can see the farms and understand how they are processing the coffees. I get to know the people who grow our coffee. I manage all the logistics and financing to purchase and ship coffees. I cup and use my experience and palate to discern what coffees are best for our portfolio. I roast all the coffee myself. And with the help of staff, all that coffee is sorted, packaged, distributed, brewed, and sold. They call us “old school.”

People occasionally tell me they want to open a coffee shop. When I hear that, it’s no different from someone telling me they want to start working out. Maybe they want to look like Mike O’Hearn. Maybe they want to serve really good coffee. Either way, it’s going to require a herculean effort over a long period of time. And if it’s not hard, you’re probably not doing it right. Sure you could cheat - like my desire to do steroids or get liposuction. But again, true satisfaction in life is the product of hard work, discipline, endurance, adversity, even suffering. Avoid all that and you might as well have stayed your ass on the sofa eating Cheetos and THC gummies with over-ear headphones, engrossed in watching someone else play video games.

Here’s the hard truth: No one likes the guy who leans into principles.

You may feel a sense of security and consistency and assuredness because of him, but he’s impossible to be around. Which leaves two choices really. Retreat inward, maybe escape to the woods. Or kill that old man. It’s likely the estimation made in my early 20s was completely wrong and I became an intolerable person. A machine, sure. One designed for work, not love.

Walking up to work this morning I thought about Isaiah and his exodus from Archetype Coffee. I’d be willing to wager that he could keep going, except it’s too hard to experience extreme, untold stress all day from work and then leave work to experience derision for not doing things the way that conventional wisdom would say a business should be run.

I operate as close to my limit as possible nearly all the time. It doesn’t take much to push me over the edge. And I’m probably teetering on the edge right now. Over the edge is the idea that no one cares, that this is all a lot of very hard and complicated work, and it’s all for nothing. On the other end of that totter are those grounding principles. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter if anyone agrees with me or not. I either live by my principles or I disappear.

There are too many people on the wrong end of that board. We need more folks who are steadfastly bound to the ideals. A few of us outweigh a multitude of them, because they are empty.

What difference does it make?

SHOP LOCAL. You see it on signs and in emails, encouraging you to keep your dollars in the community where you live, support small businesses, and (what’s not said) contribute to state and local sales tax collections. And truly, I’ve thought about this a lot over the past twenty years because I realize what a difference it can make for just one person to buy a pound of coffee from DoubleShot instead of at the grocery store. You might not think so, but each and every pound of coffee we sell is crucial and notable to our continued existence. But what’s going on at DoubleShot is a little different than other places around town.

When you shop for trinkets or for things produced by huge corporations, you have options. I might see a cool chess board at a local shop, but it’s easy to search that brand online and find a better price or a different model I like more. (If you know me at all, you are aware that I’d most likely take the idea to my wood shop and build my own chess board. If I played chess.) I might go to a big hardware store and see a drill I want, and it’s easy for me to shop online to find out if I can get it cheaper. This sort of thing happened to me in the Panama City airport. I had some time, so I was looking at wristwatches, and I tried one on that I really liked. But it was $450. Too much. I pulled out my phone and opened my amazon app and found it for $300.

Conversely, the last time I was in Flagstaff for an ultramarathon, I walked around the downtown, bouncing in and out of the shops, where I found a beautiful ceramic cup decorated with cherry blossoms, made by a local potter. They had four of them and each one was slightly different in its shape and coloration, so I picked out the one I liked best and bought it. It’s not something I could find online. And because I knew the artist’s name (Natalie Reed), I had somewhat of a personal connection to the piece, and I didn’t want to pay less than the asking price. I wanted to honor the potter’s work, and today I drink coffee from that cup and think of that story.

You can certainly shop coffee online, but if you want DoubleShot coffee, there are basically only two ways to get it, and both of them are directly from me. You might like a Java natural coffee I have from Montelin in Nicaragua. So you go online and search and find out that this is the only place you can get it. Or maybe you’re enjoying La Minita, so you do a Google search for that and find it all over the place. Some places cheaper than what I sell it for. But if you buy it, you’re going to find out how important the hand of the roaster is in the taste of the coffee. There’s only one DoubleShot, and you’ll never find coffee like ours anywhere else.

That being said, there are a lot of other reasons to consider how you spend your coffee money. When you purchase from local businesses, you’re supporting local employment. Do you appreciate the baristas at DoubleShot? You can help them keep their jobs by purchasing coffee and related coffee gear here. It may look like we’re rich and don’t need your dollars, but we absolutely do. This is a hard business, and when you’re like us and have uncompromising values, it’s even harder.

You think we’re a stalwart in Tulsa and the industry at large, and that we will be around forever after. But that’s not guaranteed. Any number of events could destroy this business. It could be eroding beneath our feet right now. There could be things happening behind the scenes that you don’t know about that could eventually mean the end of this thing you’ve come to accept as a part of your daily life. That means you should take every opportunity to buy and consume coffee from here while it’s available. And you should support the business whenever you have a need for coffee or coffee gear, because another dollar spent here instead of on Amazon or at Williams Sonoma will go further in helping us survive another year and keep that seat available to you another day.

You could walk through our shop and see a grinder you want. Pull out your phone and find it online cheaper (with free shipping, of course), and buy it from a faceless company that probably is having it drop shipped from the manufacturer instead of keeping it in stock like we do. But when you receive it and don’t know the best way to use it for our coffee, don’t know how to keep it clean and maintained, or have a warranty issue, make sure you go back to that faceless company online and ask them. Buy from me, and if you have a problem, we’ll fix it or replace it with no hassle. We’ll show you how to clean it and dial it in properly for whatever brewing methods you’re using at home. It’s called support, and it’s reciprocal.

What type of businesses do you want to support? A lot of companies are started by rich kids who don’t really have to learn how to do anything because they can hire people to do whatever needs to be done. A lot of those people aren’t in it for the love of the product, but rather investing in a company to try and increase their wealth. Are you looking to help a rich kid increase his wealth? Or do you invest in the idea of the American Dream? The DoubleShot was built one dollar at a time, one coffee bean at a time, with the hours and sweat and learning required to do everything you know us for. When I started the business in 2004, I didn’t know how to do anything. But I couldn’t hire someone to work on the espresso machine or coffee brewer when it broke down. I couldn’t pay someone to do marketing and graphic design and website development. I didn’t have the resources to seek out an interior designer or carpenter to build out the store. I had to learn to do all that myself, and put in the time to actually produce. This is a working coffee company. I built The Rookery out of a 170-year old dairy barn on purpose because I want our home to represent who we are. And we are a company with a work ethic.

I know coffee from all these years of experience, dabbling in every aspect, obsessed with every detail. And I want you to know coffee too. Because then you’ll better appreciate what you see in a bag of coffee beans and what you taste in a cup. The more you know, the more meaningful it is when you choose your coffee and consume the brew. That’s one of the main reasons I’m publishing The Coffee Purist. Not only do I expect you to come away in disbelief that so many wild things have happened over the course of my coffee career, but I hope you’ll conclude with a greater understanding and appreciation for what happens before the coffee finds its way into the barista’s hopper. (If you haven’t purchased a book yet, what are you waiting for? Pre-order one now at purist.coffee.)

Even at DoubleShot, which coffee you choose can have an outsized impact on our supply chain. All of our coffees are good, but farms like La Minita and Rio Negro are big factory farms owned by a vertically integrated Japanese tea company. I love La Minita, but whether I buy one sack or five hundred sacks of their coffee, it doesn’t make any difference because they have enough customers to sell their entire crop at a high price. When you choose to purchase coffee from some of the small farms like Bambito (owned by Priscilla), Montelin (Juan Ramon’s farm), Volcancitos (Sergio), Maduro (Ariel and Cristina), and a host of other producers you know I have a personal relationship with, it makes a much bigger impact. These coffee farmers are oftentimes producing coffee specifically for us, to my specifications. They are hoping to sell as much coffee as possible to me, because their only other alternative might be to sell it into the commercial coffee market, where they’ll make half as much per pound. Buying from a stand-up guy like Juan Ramon helps support his family, allowing him to invest more in his farm and improve his coffees, and it allows him to spend more money in his local economy. When he’s forced to sell coffee to big exporters that sell to those companies you see on the grocery store shelf, he’s often earning less money than it cost to produce the coffee. When I make a deal with a farm owner, I’m giving them a way out of that stressful cycle. I pay far greater than the commodity price, far more than it costs them to produce the coffee. I know this all sounds far fetched, but you don’t have to believe me; I had coffee producers, Cristina Garces and Ariel Montoya on the AA Cafe podcast when they were in Tulsa, visiting from Colombia, and they talked about it. It’s a long episode, but well worth a listen (or two). Go do that now: aacafe.org

Listen, I’m a country boy at heart. I grew up in the middle of a massive cornfield that stretches from Nebraska to Ohio. More often than not, I listen to country music. So it’s in my nature to be on the farm, to feel the texture of the leaves of coffee trees between my fingers and touch the soil that nourishes their roots. I become friends with the people I do business with. It’s not fair trade or some other certification, and I don’t even think of it as direct trade. It’s me forming friendships with people and developing mutual respect and trust in one another, so that they produce excellent coffees and I do them justice by roasting them properly and talking about the people who work so hard to produce them. The hard work and diligence on the farm continues in this very building.

You might feel good about your awful coffee purchase because a portion of the proceeds goes toward some worthy cause. But how can you be sure? Who is ensuring that money is used wisely? I’m skeptical of companies who put their philanthropy out front as a reason you should purchase from them. It’s playing on your emotions instead of providing you a quality product. Buy from someone you trust, like me, and I can assure you that we take care to look around and support the things I think are important. Like the arts in Tulsa. The schools near the farms we buy from. We created a micro-finance project years ago that continues to grow today and support needy farmers in Nicaragua. We’ve helped orphanages and community projects in poor parts of Colombia. We gave money to build water lines to a rural school so the kids would have clean drinking water. I paid for coffee pickers when I heard of a farmer who was ill and at risk of losing his farm. And we’re currently working on a larger project to help fund water wells in Ethiopia. We don’t normally talk about all the things we do, and I can’t even remember it all. Because I feel that responsible giving is really important, but shouldn’t be the reason you buy my coffee. It should be an undercurrent of what you feel but don’t necessarily need to know about. Buy from people you trust.

You can buy a pound of coffee off the grocery store shelf or from one of the big companies online that spend millions on marketing, and you’re supporting an industry that disrespects farmers. They lie, they cheat, and they sell the worst version of coffee on the planet. Or you can buy coffee from me, and know that your dollars are actually helping people in the tropics who need it, and the coffee will be top-notch.

What difference does it make? For every pound of coffee you buy, you’re actually making a moral decision. It doesn’t have to be that. You can just buy coffee from DoubleShot because it tastes good. But you’ll still know that I do everything I can to do the right things. Because you know me. Do you know the person who owns Community Coffee or Folgers or Dutch Bros? You may not have known that your coffee buying decisions were either hurting or helping people, but now you do.

And now you get to make that choice for yourself.

La Mancha de Cafe

Quixotic: exceedingly idealistic; unrealistic and impractical

especially : marked by rash lofty romantic ideas or extravagantly chivalrous action.

I’m what they call passionate. I rarely refer to myself in that regard, but probably ever since I refused to serve some irritating drink or kicked someone out of the DoubleShot for being an asshole, they’ve said I’m passionate. My mom probably has a different perspective on the whole thing. She says I had qualities as a kid that turned out to be good qualities as an adult. Well, that probably depends on who you ask. When people inquire what I was like as a child, she says, “Smaller.” So I’ve probably always been this way. But the common reprimand in my adult life has been, “I love that you’re so passionate, but…”

But… soft. What light through yonder window breaks? What light? Perhaps it’s the light at the end of the tunnel. When I first started running marathons, people talked about hitting the wall and then when I started running ultramarathons I realized the wall was actually a tunnel, and if you run far enough you’ll come out the other end. (As long as you do the right things.) The marathon just isn’t long enough to see the light on the other side, so they assume it’s a wall. But I’m not a marathoner. I’ve run in mountains all over the planet, mostly between rows of my beloved coffee trees. But running a business is an endeavor that has no end. It’s running toward some constantly moving goal, hoping there’s no finish line or disqualification for moving too slowly and sucking at your job. Hoping the latest tunnel isn’t a wall after all. I’ve DNF’d the Leadville 100 something like seven times, but twenty years into the DoubleShot, amid countless failures and missteps, we’re still hauling ass. So I want to unravel some of that, because our apparent success isn’t so straightforward. It’s quixotic, to say the least.

Jason Collington wrote an expansive piece about me in the Tulsa World in 2005, back when people did that sort of thing, digging into what made DoubleShot unique and how I became known as the Coffee Nazi. He didn’t call me quixotic in the story, but when he interviewed me for a follow-up in 2023 (now as the paper’s executive editor), he seemed amazed and dismayed at what the DoubleShot has grown to become for this community. He said, “You weren’t supposed to succeed. You should’ve failed.” Should I have?

I sat in the back of a taxi, rolling down the road from the airport in a town called Rionegro high up on the ridgeline above Medellin, the city lights dominating the valley and dotting the surrounding mountainsides. I sat and thought about the road trips I’d taken all across the Rockies and adjacent deserts over the past several years. Trips I’d often taken in silence, driving and thinking, working out the path of my life and how I’d gotten to where I was. What I’d done right and wrong, what I wanted, what I didn’t have yet. My successes and failures. In the cab I sat and listened to the Bachata music playing on the radio, Prince Royce maybe, and I drifted off into the theater of my mind where a pretty girl in a spicy red jumper danced flawlessly and elegantly across the bowstrings of my heart. It’s the give-and-take that makes life interesting for me. I had it all in my late twenties, except I didn’t have anything. I was building experiences through a physical strength and ability I’d honed for that very purpose. I longed for a more meaningful career and an income stream that would bolster my ability to finally land my ultimate objectives. Not absolute freedom, as it turns out; rather, earning my shot at something more fulfilling even than that.

I’d shown up in Colombia the first time with the idea that I could meet a coffee producer and buy coffee from her and roast it to serve my customers at DoubleShot. This was an extremely naive (and exceedingly idealistic) way of doing business. I Googled “coffee farm Colombia” or something asinine like that and eventually stumbled across some info for a woman named Cristina who had been trained by Willem Boot and was a certified “Q grader” (coffee taster). She appeared to own a coffee farm in Antioquia, so I sent her an email. She told me to let her know when I was in Medellin and she’d take me to the farms. Farm(s). It turned out her father was the largest coffee producer in Colombia, which at the time was the second-largest producing country in the world. I was in way over my head.

As the taxi descended into taller trees, I looked at my watch and realized I wasn’t getting any younger and hadn’t eaten in far too long. I had a half-Cuban in my back pocket, and my mind turned to the mouth-watering idea of going down on that the first chance I had. Hunger is an interesting facet of emotion and desire. I’ve always had a hunger for knowledge and self-reflection. I’ve long had a hunger for coffee perfection. I used to imagine what my ideal of the perfect cup would be like. It set into motion this quest to be good enough to recognize it when I tasted it, to know how to roast it properly, to understand the brewing variables well enough to dial it in for proper extraction. Not unlike the life I’d built outside coffee. Learning, training, experiencing, always searching. But now I don’t idealize “perfection” as something necessarily immaculate; rather, I keep my awareness open enough to recognize something unique when it comes my way. And, as I dig deeper, having the ability to discern when I’m in the presence of the incomparable. But I use my nose to smell out when something isn’t what it appears to be. I use my mouth to flesh out what it could be. I search for its quirks, the soft spots, even the things that people might call “flaws,” and I find pleasure on the edges.

Once I drove a similarly descending route from Flagstaff to Sedona, not into the city of eternal springtime, but out onto the high desert full of yogis and eccentrics. I can admit to being a bit eccentric myself, so I’m not a hundred percent out on that scene. But with no coffee trees in sight, I decided to give a local roaster the chance to show me their stuff. I walked up to the counter and ordered an americano: “Leave room for Jesus.” I don’t like my coffee or my relationships watered down by trivialities or practicalities. Of course the coffee was disastrous. Because it takes a lot to make that relationship right between producer and roaster, terroir and climate, variety and process, fermentation and drying, time and temperature and pressure. A proper coffee is hard to come by. That’s why I always say when you have that moment, the moment of elation, take it all in. Stop and relish what’s happening and how rare it is that the stars aligned.

Two of the fairest stars… having some business, do entreat her eyes to twinkle in their spheres ’til they return. The eyes are the windows to the soul, they say. One can impart an awful lot of information through the eyes. One look can be worth a thousand words. It’s a connection I found with Juan Ramon Diaz in Nicaragua. I suspected that he and I were brothers of some sort, but when I saw the look of devastation and courage as he held back the tears of his father’s mourning, I knew his soul. I thought about what I was even doing in Nicaragua, trusting a friend of a friend and on down the line to help me stay out of harm’s way and be honest with me and parse out what it means to produce excellent coffee, to earn proper wages, and to be in a relationship. On a wing and a prayer, I took my shot. I introduced myself as genuinely as I knew how, stayed out of the trivialities that sometimes plague relationships, and promised complete transparency and brutal honesty. That’s what you want, right? Brutal honesty. No, probably not. Not unless you’re the rare one whose straightforward demeanor demands nothing less. And that’s how I operate. No one ever accused me of being “too nice.” So I commit, mostly out of unrealistic and impractical ideations of commerce and friendship coalescing into a bountiful outcome for all. And then I find out one of these coffee farmers is out swiping on coffee Tinder looking for a date to the prom. I’m not interested in a date. I’ve trained my entire life for this moment and I want a commitment to work together at the highest level, to inspire one another to be better, to admit our failures and maybe even to admire the flaws. The “imperfections” are what make it. And I can see it in your eyes.

I witnessed the birth of Maduro throughout my early days in Antioquia. That relationship with Cristina blossomed into a full-blown friendship in which her husband, Ariel, agreed to do some experiments with coffee from his farm, and then more experiments until we created Colombia’s first natural. I may be quixotic, but greatness is rarely found by the staid.

I walked through the coffee trees on the side of a mountain in Guatemala, where I’d disappeared into a sea of chicken buses and Mayan villages and earthquake ruins. I popped a cherry into my mouth and tasted the soft, sweet, stimulating flesh that I’d purloined from the limbs of another’s rightful harvest. A harvest neglected through a years-long relationship in which fallow fields yearned to be cared for in a way that’s generally impossible without a transfer of ownership. I birthed two coffee seeds from the pulp in my mouth, twins I quickly adopted as my own, with the intention of raising them into the best two trees I could in a foreign climate, something I know very little about. But you surely know by now that ignorance is not an excuse that keeps me from full-on commitment.

The microwave sounded its three long beeps and snapped me out of my trance. I’m that weirdo who nukes an Arby’s roast beef sandwich for breakfast at 4 a.m. on race day. I thought about the hours that lay ahead of me, the miles upon miles of trails I’d tread. The anticipation of quiet but for the sounds of breezes through trees and waters flowing, the bird’s call, my breath and footfall. As each mile passed, the societal norms set upon me would melt away and I would transform from person to sapien, and then ascend into the state that resides prominently within me: the lion. Unleashing that quiet confidence where there is no future or past, and my immediate awareness sharpens to a razor’s edge. And what does that have to do with coffee or business? It’s the thing I hide away when I smile and nod; that mysterious thing you sense when you look into my eyes and feel nervous. That primal state which drives our core values and disallows anything less than absolute respect and conviction. In a general sense, Collington was right. This is no way to run a business. But I play the long game. I methodically and unwaveringly stand my ground, first earning your respect before earning your allegiance and indulgence. You wonder if the lion will speak. One lion may when many asses do.

En boca cerrada no entran moscas. That’s a proverb I learned at Galesburg High School in a class that taught me root meanings of words, suffixes, prefixes, and the like. Turns out this was one of a jumble of proverbs spat out by Sancho in Don Quixote, novel by the great Cervantes: “It’s a sin to belie the devil: but misunderstanding brings lies to town, and there’s no padlocking of peoples’ mouths, for a closed mouth catches no flies.” I tend to tilt at windmills. The mayor, other coffee roasters, Starbucks, sometimes even the customer. But my windmills are idealistic imperatives that get usurped on occasion by politics, greed, misinformation, or ignorance. The black-and-white of wrong and right can sometimes be perspectives that change over time, situations that I can hyperbolize in a momentary overconfidence. But sometimes being exceedingly idealistic is what’s needed in a society seized by mob-mentality in which groupthink forgets about our lack of egalitarianism. Am I right or am I wrong? And is someone with money just trying to exert their financial superiority into societal subjugation? That’s what gets my hackles up. So I fight for an impractical leveling of the playing field. It’s quixotic, sure, but I’d rather have a mouth full of flies than be a mealy-mouth.

I walked through Maracay, the farm in Colombia where we get our Pink Bourbon and washed Caturra, among other things, and I observed that some trees had bronze leaf tips while others had green. This is normal, but not usually in a lot of trees that are supposed to be the same variety. It’s like inspecting the troops and finding them all wearing different colored hats. I was asking the farm manager about this and then I stumbled on the most remarkable thing I could imagine: a coffee tree dressed entirely in red. Red cherries, sure. But this one had red leaves, which I’d NEVER seen before. A true anomaly, something so remarkable growing in what can only be described as the bosom of the woods of some royal forest. A Kimberly. Pristine. I stood and looked in awe. If I profane with my unworthiest hand this holy shrine, the gentle sin is this: my lips, two blushing pilgrims ready stand to smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss. I touched it and felt the texture of its leaves, the structure of its limbs, its strength and suppleness. The forbidden fruit I haven’t tasted. But I intend to just as soon as it’s ready.

I saw two robins out on the lawn, one plump and round and the other lean and mean. The smaller of the two hopped irregular circles around the larger, a dance of daring and determination. The female avoided the advances of the male, at times dashing for him as he retreated and then resumed his pursuit. Once in too close, the two leapt into the air, colliding twenty feet above the earth, abreast, dive-bombing back to the grass and the ritual continued. She lets him in and then retreats, methinks. He hops around the perimeter, waiting for another chance as she preens her wings and puffs her mighty breast. Dancing has never been my forte. It was against church rules when I was growing up, so I developed two left feet. In college I was required to take a dancing class called Rhythmic… something, and not even my then-girlfriend wanted to be my partner. All that said, I understand the dance that exists between two souls when they meet amid an innocent gaze. I know the dance of the barista, juggling portafilters and steaming pitchers, navigating drinks and folks between the refrigerator and sink. I know the dance of the roaster more intimately than anything. That’s a sacred dance.

I love coffee. I chose to love coffee a long time ago, and to me that kind of love means getting to know it more and more all the time, even through its seemingly endless changes. It means holding it close, even closer in challenging times. But something else happened in the early days. I fell in love with coffee the way one falls in love with their soul mate. I remember how it lit me up the first time I had a meaningful experience with coffee, and how it still lights me up thirty years later. It’s that combination that makes it work for me over the long-haul. A daily decision and a deep affection.

Joe Holsten was probably the first person to actually grasp what I was doing with coffee. He sat down sheepishly on a stool as I commanded the bar and slung commentary and coffees with equal bravado. Joe. A fitting name, for coffee’s sobriquet. He probably ordered a doppio and I probably looked at him side-eyed. I pulled something spectacular out of the grouphead and felt that it was too good to give away, so I drank it myself. Then I pulled another equally godlike shot and told him he was lucky that the weather was just right for espresso and the shots were running toward eternity. I went back to my romantic discourse until someone whispered, “Joe is crying.” I looked over and Joe was sitting on the floor against the crema-colored wall, cradling the demitasse in his hands with tears rolling down his cheeks. “What’s wrong, Joe? No good?” He didn’t have the words at the time and I probably didn’t grasp the certainty with which he affirmed my mission. But today I hear whispers of intensity and desperation echoing in my head; whispers from the ages, like winds flowing up out of a cave where the soul resides. Pure, passionate, primal words that affirm my life’s mission and steel my dedication with even more fortitude and forbearance. I know what I want. It came to me in whispers.

I fell asleep while I was eating dinner Friday night. I woke up staring into a plate smeared with the residue of mashed potato with half a New York strip and a handful of Brussels sprouts. I used to fall asleep in the cafe, sometimes on the rubber mat in front of the three-compartment sink. I’d be washing dishes at some ungodly hour and decide to just lie down on the floor for a minute and then I’d wake up and realize it was time to open again and I hadn’t finished the dishes from yesterday. I know what it means to work a lot. People used to brag to me about how many hours they worked and how few they slept, but I knew that was a fool’s errand and I was on that very path to destruction. My friend Fred used to say he was burning the candle at both ends. He died young. But I understand his urgency to get as much done as humanly possible. This life is too short and I have too many ideas and aspirations. I acknowledge here and now that it’s impossible to achieve everything I set out to do in one lifetime. And so I hope I get another go. I hope I fulfill some of the gritty stuff and get a restart with some of those things already in the bag. Of course I don’t believe in that kind of thing, so I’ll consider Nietzsche’s “eternal return” and stay the course. I’ve trained for the past twenty-nine years for one dream I’ve yet to realize. So I decided it’s time to tie that knot.

We are on a precipice. The changes that are about to take place in my life and the life of DoubleShot are monumental. I predict that this time next year we will look back in awe at how different everything is. This is the end of an era, my friends. For all the good and bad, all the pain and hardship and victories and defeats, now is the time to step forward and grasp at the chance to fulfill the ultimate purposes for which I set out as a mere child. My methods have been quixotic, to say the least. But always forward. I count my losses as lessons and the lost as honored ancestors, and I do not dwell on my victories. Is this about absolute freedom? Certainly not. It never has been.

Don Quixote, imagining he were disdained by a beautiful queen and his love unrequited, decides to go out into the wilderness and do penance in order to prove his madness for the queen despite not being rejected, so that she might understand the lengths that he might go should she actually reject him. He asks Sancho to stay and watch him for three days so that he can go and report Don Quixote’s insanity to the queen. Sancho asks Don Quixote, “What more have I to see besides what I have seen?” To which Don Quixote replies:

“Thou hast seen nothing yet.”

Black Dog and the Buffalo Nickel

If you’ve been paying attention at all the last few years, you likely know that I love the Wichita Mountains. I mean, really, that place is like nowhere else I’ve ever been, and I’ve been a lot of places. It’s a wildlife refuge, so I feel safe there. And that wildlife refuge wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for Teddy Roosevelt. Well… let me back up. This entire country was a bit of a wildlife refuge until European settlers decided to round up the natives and rid the continent of its furry, four-legged fauna. The Wichita Mountains were originally established as a forest reserve by President McKinley in 1901. Then Roosevelt designated it as a game preserve in 1905. And this is where things get interesting. (Again.)

Let me back up one more time. This continent was crawling with wildlife, even into the 1800s. If you’ve ever been to Africa and seen lions walking down the roads and giraffes craning their necks alongside tall trees, you get a vague idea of what the Americas might’ve been like back in the day. I read a couple books about the Corps of Discovery Expedition of Lewis and Clark (Undaunted Courage by Stephen Ambrose is a classic), and their boat ride out west from 1804 to ’06 was nothing if not a testament to the diversity and breadth of animals ranging across the continent. Current estimates guess that there were sixty million bison roaming North America at that time. By 1890, there were sixty million people living in the US and only 541 bison remained. Quite a trade-off.

I’ve been told that bison are not buffalo but I disagree. Sure, their scientific name is Bison bison bison, generally shortened to “bison.” But the Oklahoma state wildflower is the Indian Blanket, which bears the scientific name Gaillardia pulchella, and no one gets upset that we don’t call it gaillardia. I read a book by Stephen Rinella called American Buffalo and he makes the argument that the two names, bison and buffalo, are used interchangeably, and both properly. Historians believe the name buffalo came from the French, who were trapping and hunting all over this continent before colonization. Beef, Frenchified: Boeuf. In 2019, I had the rare pleasure of seeing the large-but-elusive “bison” in the Baba Budan Giri Hills of southwest India. The beast rose up onto its hind legs, a prodigious body on spindly limbs, leapt over a fence, and disappeared into the forest. But these aren’t bison at all; they’re gaur (Bos gaurus). My friend Jaime Abel usually drives me around whenever I’m in the Colombian countryside where he manages a few cattle ranches, one of which raises water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) for milk (and mozzarella). But in Spanish, Jaime always reminds me to be careful milking a buffalo because it’s a lot different than milking a buffala. So let names be names. Buffalo in the U.S. are bison.

—

There were a few bison caged up in zoos at the end of the 1800s, which is pretty much the only place an American could see one by then. One very famous bison was called Black Diamond, a big bull buffalo housed at the Central Park Menagerie (now called the Central Park Zoo). This guy was rumored to be the model for the bison on the obverse of the 1901 ten-dollar bill with portraits of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on either side. (This rumor has since been quashed, as the model for the engraving was apparently based on a stuffed bison on display at the Smithsonian in the late 19th century.)

Black Diamond was also rumored to be the model for the reverse of the buffalo nickel. In 1904 President Roosevelt expressed his dissatisfaction with the artistic state of the American coinage. Thus began a years-long effort to redesign a few things. And eventually, in 1913, the buffalo nickel went to mint. This was designed by James Earle Fraser, the guy who sculpted the “End of the Trail” statue that was in the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. (Subsequently the statue was tossed into a mud pit along with other works of art from the exposition, then rescued and displayed in a park in Visalia California until it was deteriorated by weather and given over to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City in the 1960s, where you can see it today.) But Fraser never said Black Diamond was the model for the nickel, and further research points toward another bison that was kept at the New York Zoological Park (now called the Bronx Zoo) named Black Dog.

That reminds me of a story. I was in Panama a few years ago, hanging out on a coffee farm where Gesha trees grow as thick as the hairs on a bison’s tail. The top of the farm had an orange tree that turned out to be sour orange (an orange so shockingly sour that it’s almost an addiction) and the bottom of the farm had rows of giant drooping flowers that released an intoxicating perfume at sunset which apparently contains a bit of narcotic that helps stinky people sleep. There were children playing on the dirt roads and a black puppy trailed along with them. So I asked them in my most formal Spanish, “Como se llama tu perrito?” To which they replied (in their best English), “Blek Dog.”

So I don’t know why this Black Diamond was so popular and why he was stealing everyone else’s thunder, but these are the facts.

—

Back to Roosevelt. Not only was he pissed about how crappy our coins looked, he was also pissed that we’d decimated the bison population across the entire continent. So he, along with the American Bison Society, set out to establish a new herd in the newly minted Wichita Forest and Game Preserve. I recently found a publication from the American Bison Society from 1908 that details the political, logistical, and practical events that took place in order to move bison from New York to Oklahoma. In October of 1907, fifteen bison at the New York Zoological Park were herded into individual wooden crates built specially for the project and loaded onto a train, and seven days later arrived in Cache, Oklahoma where the crated animals were off-loaded onto wagons and carted twelve miles across the prairie to the new bison range. The big breeding bull in this new herd just so happened to be Black Dog himself.